Who Owns The MLA?

The MLA is its membership, but that membership cannot be trusted with publishing revenue.

Last week, I traced how the Modern Language Association (MLA) Executive Council, in the report rationalizing its suppression of a Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction (BDS) resolution, adopts an extreme interpretation of Corporate Social Responsibility, one closely associated with Milton Friedman and Chicago School Economics. The Chicago School from its origins has been hostile to and destructive of humanities disciplines, and thus I see the MLA’s recent emphasis on the logic of fiduciary review derived from Corporate Social Responsibility as deeply damaging to all those who the organization claims to serve and represent.

Amidst protest at the annual convention this weekend, MLA President Dana Williams said, “The association is the membership, we want to reiterate.” But in recent weeks the MLA leadership has not been consistent about what exactly the organization is.

As many people noted following my last post, the MLA is not a corporation, which makes its adoption of Corporate Social Responsibility somewhat more galling. Milton Friedman himself does not advocate for the extension of his doctrine beyond the structure of the corporation and, in fact, specifically cites schools and unions as organizations for which his doctrine would not be coherent.1

That said, since Corporate Social Responsibility became “settled law” for publicly-traded companies in the 1980s, there have been efforts to expand that legal valence to, for instance, municipalities, public schools, and government agencies, forcing their leaders to prioritize economic forecasts and revenue maximization over their public service missions. Executives at some non-profit organizations have been all too eager to adopt corporate definitions of fiduciary responsibility.2

So, the MLA is hardly unique.

But even in states where fiduciary law has been nudged beyond what Friedman originally proposed, enforcement stands on shaky ground. And, in fact, even for corporations, fiduciary law is not as settled as it was at the height of the Chicago School’s bipartisan influence. Prominent companies of the “New Economy” (for instance, Apple) have lobbied hard for an interpretive shift from “shareholder primacy” to (the considerably less enforceable) “stakeholder primacy.”

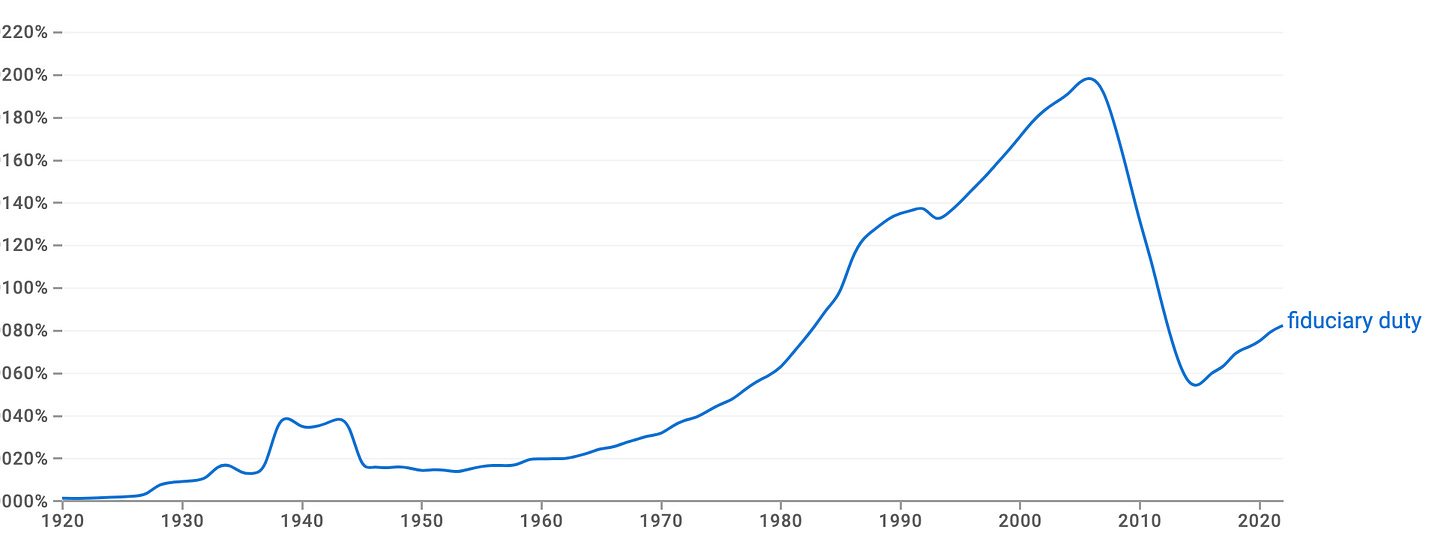

As you can see in the below ngrams (as well as the one from my last post) invocations of fiduciary duty, responsibility, and review declined sharply after 2008, as even neoliberals realized strict reliance on economic forecasting of shareholder interests wasn’t so foolproof.

Which is all to say, with even greater emphasis, the idea that the Executive Council is bound by its fiduciary responsibility to prevent MLA’s Delegate Assembly from voting on a resolution, I find utterly unserious.

And if Director Krebs and the Executive Council want MLA members to support their extreme interpretation of fiduciary responsibility, they should show their work. How has the fiduciary review been documented? And what are the models and metrics used to forecast the dire consequences of a resolution being debated by members?

The absence of specificity and transparency in the December 16 report, commented upon by both the authors of the BDS resolution and a coalition of eight former MLA presidents, is the standard two-step of neoliberal governance:

Step 1: Based upon our internal economic forecast we are contractually bound by fiduciary responsibility.

Step 2: We cannot divulge the method, model, or even detailed results of said economic forecast because it is proprietary, and broad public knowledge might compromise our ability to capitalize on its prescriptions.

I have encountered this two-step on many occasions in my decades of studying economics and finance, often with the same patronizing addendum: Why don’t you just trust the technocrats, you useless humanist.3

Though the MLA’s Executive Council’s chosen interpretation of fiduciary responsibility goes far beyond anything advocated for by Milton Friedman (whose doctrine is the foundation for contemporary fiduciary law), I think it’s revealing to test that interpretation against the original.

The Friedman doctrine relies upon a hierarchy of capital ownership over institutional decision-making. Friedman characterizes corporate executives who cave to protests as “spending someone else’s money for a general social interest.” While Friedman does acknowledge that the money being spent in the name of social justice might be that of consumers (via rising prices) or employees (via reduced wages), he argues that these effects are hard to predict and that standards of consumer primacy or labor primacy would be incompatible with a corporate structure (in which the business’s financial interests are frequently oppositional to those of consumers and rank-and-file workers).

But publicly-traded companies are owned by shareholders, who are not only directly lending capital to the corporation through the stock market, but are also indirectly appointing the executive (usually via a board of directors).

In the most direct and traceable way then, according to Friedman, the executive is spending shareholder’s money, and if they wanted their money to be spent on social causes, they could do so without the paternalistic aid of an executive.

Characteristically, the Friedman doctrine returns to that which is most sacred across Chicago School dogma: the property rights of the investor class.

As much as I might disparage the very idea of securitized property, any coherent invocation of fiduciary responsibility requires us to ask whose money is being projected and hypothetically protected in economic forecasting.

In other words, who is the fiduciary review being performed on behalf of?

In the “Fiduciary Considerations” section of the December 16 Report, the Executive Council wishes to be absolutely clear that the answer to that question is not MLA members.

The MLA has a very different financial profile than most of the other humanities member organizations. While we, like they, collect dues and conference registrations, these funds are only a small portion of the revenues on which the MLA relies to pursue its mission in publishing, convening, professional development, and advocacy for humanities teaching and research. Fully two-thirds of the operating budget of the MLA comes from sales of resources to universities and libraries, including the MLA International Bibliography.

The tautological, paternalistic logic of these sentences baffles me. Again, it can’t be taken seriously. The Executive Council is claiming it cannot allow its membership to democratically consider the BDS resolution because membership dues are not a sufficiently large revenue stream to make members the primary stakeholders in their member organization, whose other revenue streams must be protected from and for MLA members, in order to deliver to members what they actually need, which is neither democratic authority nor, apparently, reduced membership or registration fees.

The more times I read this passage, the more it becomes to me: We need our publishing business to pay for our publishing business.

So, if MLA members don’t have final authority over MLA publications, because their dues are too paltry to claim ownership of them, who does? Who is the Executive Council’s fiduciary review on behalf of? Who is its fiduciary duty to?

I realize “the MLA is not a labor organization,” nor a school, but if it does not share missions with either of those institutions, and therefore share Friedman’s exception, what the hell is it?

As Kelly Grotke’s work shows, presidents of private colleges and universities sometimes adopt corporate fiduciary standard, either because they are pressed upon them by boards of trustees or because such adoption shields them from pressure to divest endowments.

“We acknowledge that phrases such as ‘fiduciary review’ and conversations about revenue can sound callous in the face of atrocity, especially when framed as though our aim is to protect revenue alone.”