There’s a moment in Charles Ferguson’s Inside Job (2010) that haunts me.1 Ferguson is conversing with Eliot Spitzer, the former New York Attorney General, in the early stages of rebuilding his career as a commentator after resigning his Governorship.

Ferguson hypothesizes that the “level of criminality” in finance is “somewhat distinctive,” specifically by comparison with the other famously-lucrative sector of the millennial economy: “high tech.” Spitzer agrees with this premise, adding, as explanation, that “tech is a fundamentally creative business, where the value generation and the income derives from actually creating something new and different.”

Even when I first saw Inside Job, which certainly has it charms, this exchange made me cringe. By the time the film hit theaters, the first fintech-triggered flash crash had already taken place, and the unbanking of America was well underway. Precarious demographics first and foremost - the unhoused, the undocumented, sex workers, abused women and minors - were being forcefully converted from cash to non-FDIC-insured and largely unregulated fintech platforms, where their limited funds could be siphoned or seized without explanation and with little recourse.

By the time Ferguson and Spitzer were having their conversation the distinctions between finance and tech were already blurred to the point of being impracticable, in part because both had been mostly subordinated to the penumbra of private investment funds.2

Ferguson and Spitzer’s descriptions are exemplary of a beltway orthodoxy that was being broadcast and absorbed throughout the land, and which persisted, mostly unchecked, for the next decade.3 These tech guys were getting unfathomably rich, sure, we were told, but they weren’t like the bank executives, or the insurance giants, or the telecom syndicates, or the oil barons, or the landlords, they were creating a more just and verdant world for all while they accumulated, and shouldn’t we be grateful.

The illusion that post-crash Silicon Valley was not just pre-crash Wall Street dressed up in a custom-printed hoodie has had surprising endurance. Matt Damon, who narrates the jeremiad of Inside Job with appropriate zeal, became, a decade later, the spokesperson for Crypto.com.4 His conversion from financialization muckraker to fintech evangelist exemplifies the widespread failure to recognize that what motivates fintech entrepreneurs is exactly what motivated the “innovators” of credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations: the evasion of financial regulations, and precisely those financial regulations that were designed to prevent economic crises by discouraging fraud.

In some cases, the financial innovators and the tech entrepreneurs are the very same people. Peter Thiel started his career as a derivatives trader for Credit Suisse, whose history, as Duncan Mavin puts it, “reads like a long list of relentless wrongdoings” leading up to a distressed merger in 2023. Elon Musk also began his career working for a multinational bank during the securitization boom, and quit because the CEO didn’t see the foolproof genius of his arbitrage scheme involving the sovereign debts of developing nations. Musk founded the original X.com with the express ambition of growing it into the “Amazon of financial services,” an ambition which was thwarted, at least in part, by the Glass-Steagall Act, before it was repealed in the name of financial innovation.5

Musk and Thiel are, of course, the two most well-known members of the so-called “PayPal Mafia,” men whose fortunes and influence derive largely from the sale of their fintech platform to eBay in 2002, after which they became key figures in the startup culture of Silicon Valley. Both are also, notably, megadonors and advisors to the current administration, which also employs at least two other prominent PayPal alums: David O. Sacks (COO) and Ken Howery (CFO & also a co-founder).

Like Musk’s extralegal Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), Sacks has been given an unofficial title, “A.I. & Crypto Czar,” and, also like Musk, regards this as unchecked power to dictate to legitimately-established government agencies like the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

The PayPal Mafiaosos are also long-time techno-utopians who have recently adopted an anti-democratic and, indeed, post-nationalist flavor of political-economic extremism, members of what Gil Duran has dubbed “the nerd reich,” openly fantasizing about acceleration towards feudal “network states” in which each imagines himself as a kind of cybernetically-enhanced genius warlord.6

The PayPal Mafiasos are all paper billionaires, all of whom have complex and purposefully opaque networks of business interests, including investment firms at which they are founders and principals, and companies which rely on government contracts and/or regulatory arbitrage. Of course, none have placed their assets in a blind trusts or created any illusion that they are not using their government positions to gain an edge for their private enterprises and portfolios.7

And they are all closely associated with companies long on potential, but short on performance. Tesla’s 2024 profits were 1.5% of its Market Cap, and 40% generated by selling regulatory credits rather than actual cars and “trucks.” Palantir’s 2024 profits were 0.2% of its Market Capitalization, even after the recent selloff which Thiel and his fellow executives are leading.

A decade of overconfidence in their ability to prophesize has, I believe, induced all of them to lean way out over their admittedly long skis, including in exactly those technologies which Sacks is allegedly czar-ing. They bet long on simultaneous, revolutionary disruptions to the U.S. labor and money markets through mass adoption of crypto and generative AI.

Thus far, these disruptions have failed to manifest. The questions which they, and many paper billionaires like them, now face, is not only whether these disruptions will ever happen, but, more pressingly, how much additional investment will be required to make those long bets pay? Can paper billionaires raise the capital needed without crashing the stock prices of their signature companies or, worse yet, inciting a full-fledged financial crisis.

Here it’s useful to review John Kenneth Galbraith’s common denominators of speculative bubbles:

“the extreme brevity of financial memory”

“the specious association of money and intelligence”

“the thought that there is something new in the world”

“debt dangerously out of scale with the underlying means of repayment”

The private fund industry rushed, euphorically, to pour resources into AI developers and the platforms they presumed would benefit from AI development in 2021, presuming that market-ready applications would be primed for blitzscaling by now. “The biggest risk with AI,” Thiel said, as recently as December, “is that we don’t go big enough. Crusoe is here to liberate us from the island of limited ambition.”

But individual consumers, target sectors, and institutions (including governments) have been slow to embrace and adopt, in some cases because the utility of the applications is not as obvious (at least not yet) as the market-makers had anticipated.

The trouble has been clear to many (including, I presume, the PayPal Mafia) for at least a year. Financial trendsetters like Bain Capital and Goldman Sachs have even started openly questioning whether (or, at least, when) investors will start seeing returns on the bets they made during the market peak. And individual engineers inside teams at Microsoft, Google, and OpenAI have reported (often anonymously) that the training of LLMs remains slower than their companies (and investors) expected.

In short, speculative euphoria is draining from the AGI/fintech boom and the broligarchs need to find a way to prop up their utopian promises.

Galbraith identifies three ways over-leveraged speculators maintain the illusion of a bull market even after the correction has begun:

proximity to and control of capital transactions

“foolish indifference to legal constraints”

disguising debt as an asset

If you want to get rich before the bubble pops, make a beeline for the payments systems, defy the law, and never admit how much money you owe. Default if necessary.

The crises which Galbraith based his theory upon, originating in the U.S. from the 1870s to the 1980s, were exacerbated primarily by bankers, who were uniquely positioned to cook the books and massage public confidence to keep the bubble from popping, at least for a little while. The bottom always fell out eventually, but bankers patched things together for a little while longer, and in some cases were able to minimize losses or even, in the parlance of the subprime crisis, attain a net short position without finding themselves in, as Galbraith puts it, “moderately uncomfortably confinement.”

The PayPal Mafia who, as they have demonstrated throughout the constitutional crisis of this past month, have an expert understanding of the administrative apparatuses of the U.S. financial system, came up with a workaround which none of the bankers (save, arguably, J.P. Morgan in 1907) tried: hostile takeover of the regulatory state.

There is no better perch from which to execute Galbraith’s bubble-prolonging playbook than the shadow presidency. Not only can Musk now flout legal constraints with utter indifference, he could divert public funds directly into his most illiquid businesses, and use asymmetric information to diversify and buoy his investment strategies. From the data-mining operation of DOGE, Musk appears primed to create quite possibly the largest and most comprehensive financial model in history, one which he likely envisions as the key to that long-deferred dream of turning X into a financial services company.

So, this is about money. Aren’t you glad it took me two thousand words to make this earth-shattering point.

Well, no. That’s not exactly it.

The PayPal Mafiosos, prior to the hostile takeover, were never in any danger of going broke. There is no imaginable circumstance, regardless of the outcome of the 2024 election, in which they would have ever been prosecuted, had their fortunes confiscated, or their business bankrupted. They are already too interwoven with the U.S. government, already too big to fail. The fintech bailout would’ve been (and, I believe, still will be) as big, as bipartisan, and as “no strings attached” as the TARP bailouts were in 2008-2009.

What they fear is not loss of capital, but the loss of reputation.

“The investing public is fascinated and captured by the great financial mind. That fascination derives from the scale of the financial operations and the feeling that, with so much money involved, the mental resources behind them cannot be less. Only after the speculative collapse does the truth emerge. What was though to be unusual acuity turns out only to be fortuitous and unfortunate association with assets. Over the long years of history, the result for those who have been thus misjudged (including, invariably, by themselves) has been opprobrium following by personal disgrace or a retreat into the deeper folds of obscurity”

John Kenneth Galbraith

For two decades, Musk, Thiel, and several of their Silicon Valley peers have sustained that illusion which Charles Ferguson and Eliot Spitzer articulate in Inside Job, that they are innovators, value generators, and creators. They are the founders and architects of the new economy. That status they are willing to stop at nothing to sustain.

And they hope that by capturing and then dismantling the New Deal regulatory state, they will be able to preserve that status for posterity.

But they won’t.

“Financial genius comes before the fall,” as Galbraith puts it.

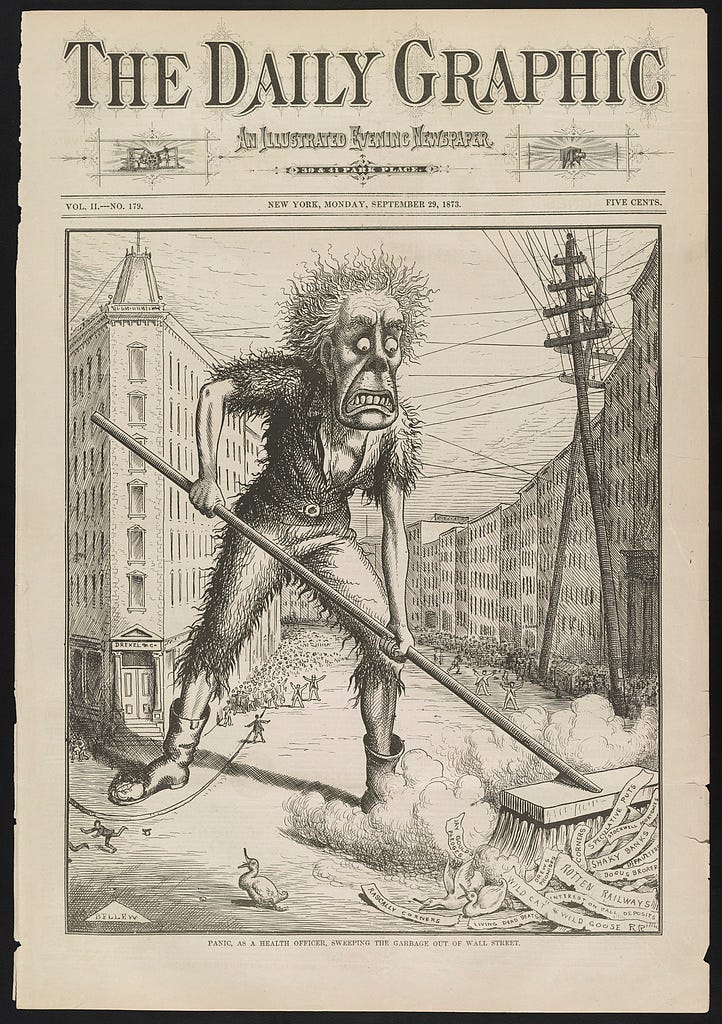

Their problem lies in what that regulatory state was erected to prevent: panic.

Inside Job would win the Oscar for Best Documentary in 2011 and was one of the twenty highest-grossing documentaries up to that time, but by comparison to The Big Short (2015), which almost single-handedly turned private fund managers, arguably the architects and certainly the beneficiaries of the 2008 meltdown, into heroic “activist investors,” its cultural impact has been pretty marginal.

But Inside Job has had a long afterlife on streaming services and, perhaps as importantly, in classrooms. I suspect it is the most-assigned documentary of the 2008 global meltdown, embraced by instructors across a wide range of disciplines. I have personally known not only humanists, but also sociologists, economists, psychologists, and finance professors who regularly use the film (or at least selections from it) in their classes.

Usually called venture capital when headquartered to the west of the Mississippi, hedge funds to the east, but, at least for the purposes of my topic today, identical in effect. In the last ten years, the number of private funds (as reported by the SEC) has more than doubled, with venture capital firms specifically increasing their numbers by 600%. In aggregate, according the the most recent SEC filings, private funds control $23 Trillion in assets. For comparison, the market capitalization of the entire U.S. oil & gas industry is about $2 Trillion.

In the forthcoming series of podcast episodes I’ll be pointing to a particular moment in 2021 when I think the orthodoxy began to break down.

The “Crypto Bowl” of 2022, during with Crypto.com and FTX (as well as several fintech companies) aired ads, is now reminiscent of the 2006 ad by subprime lender, Ameriquest, which went bankrupt the following year.

Glass-Steagall would be repealed at the behest of Citibank just as X.com was negotiating the merger with Thiel’s Confinity that would create PayPal.

Regardless of how successful this administration is at dismantling consumer protections, deposit insurance, leverage limits, and the independence of the Federal Reserve, one New Deal invention which has already been made a relic is the taboo against “insider trading.”