Putting The "If" In "Enrollment Cliff"

Academic administrators are being prescribed Ponzi austerity by consultants who work for EdTech investors to solve a hypothetical demographic "crisis" with unsettling racist dog whistles.

I posted a little thread on Twitter this past weekend. It got more traction than I expected.

I genuinely did not expect this to be a particularly hot take with my mutuals. I certainly am not the first person to poke holes in the “enrollment cliff” myth. But this was new information for many, and my thread soon jumped the guardrails of my social media niche (with all the harassment that entails in the Elon era).

In order to avoid feeding the trolls, I muted the thread for 12 hours, and I’m still reluctant to engage too much on the platform, even with earnest interlocutors, for fear of attracting more bots, blue-check bros, bad faith, and ad hominem. In the interim, however, I have also received a flurry of private messages from colleagues and organizers with follow-up questions.

In this (and probably one additional) post, I’m going to critique the enrollment cliff, but with emphasis on links to other researchers and resources.

The basic hypothesis of the enrollment cliff is that higher education is on the precipice of (yet another) crisis. During the 2020s a combination of shifting demographics and shrinking demand will create an unprecedented scarcity of prospective college students and in order to survive this inevitable contraction, institutions need to “right-size,” that is, aggressively cut costs, especially “underperforming” programs, “outdated” infrastructure, instructional and academic support staff.

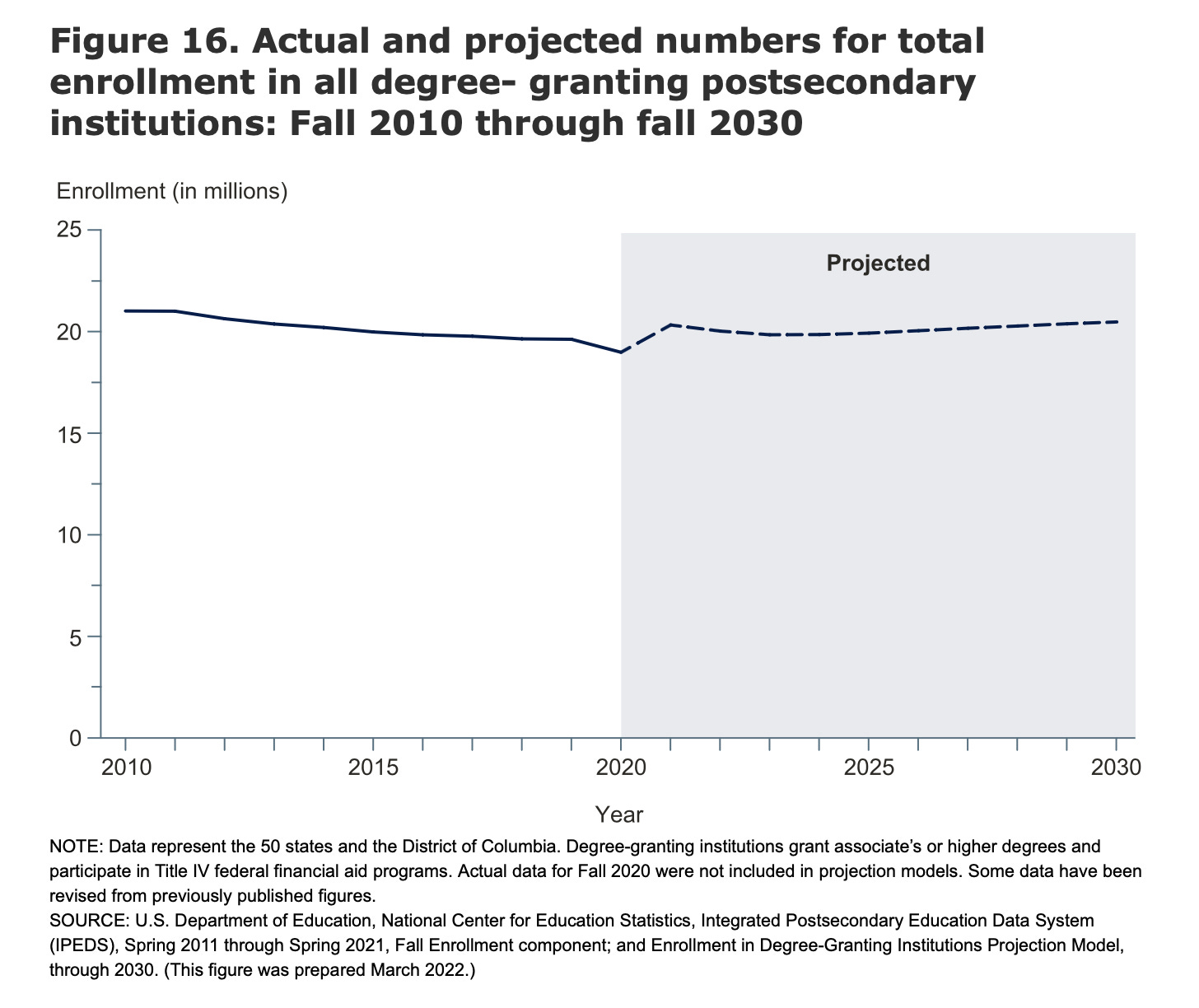

One thing you’ll notice if you search “enrollment cliff,” is that nearly all the results will either come directly from for-profit education consulting firms, for-profit educational technology firms, or people with ties to those firms (or to tech-centric think tanks) writing op-eds for industry publications like Inside Higher Ed or being interviewed by mainstream media. They will be replete with crisis-mongering, but one thing they definitely won’t show you is this:

This projection from the National Center For Education Statistics (NCES) continues to show no cliff. In fact, one might go so far to say that it is characterized by its very clifflessness. The above graph includes both undergraduate and graduate students, but if you look exclusively at undergraduates, the news is (imperceptibly) better, an increase of 9% over the next decade (as compared to 8% overall).

Of course, no projection is perfect, even one based on large government data sets going back to 1869. CTAS Higher Ed Business instead looked at population data and arrived at roughly the same conclusion:

Raw data from the CDC National Center for Vital Statistics show very stable cohort sizes for prime age college populations up through 2036. The prime age 18-23 cohort numbered 23.7 million in 2018; in 2036, it will number 23.5 million. There is no cliff. Most businesses would be grateful for such stability in their customer base.

The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education projected only U.S. high-school graduation rates. They do forecast a very gradual decline, roughly 5% over a period of 18 years (!!!). Not only is this hardly a “cliff,” as CTAS points out, as a basis for projecting college enrollments, “it undercounts the pool of prospective undergrads” because it counts only “on-time graduation” and takes little interest in international or other growing non-traditional student populations.

So, if the projections by these agencies range from weak growth to stability to very slight decline, why are administrators preaching cliffs, crises, and cuts?

In the next installment, I’ll look at the consultancies and ask, who is serving whom?

How do you figure the changing demographics will affect the model of the university? The current one is Humboldtean, namely a dual emphasis on teaching and research.